Preventing Meningitis, Meningococcal and Pneumococcal

- DO NOT share drink bottles or drinking glasses.

- DO NOT share food.

- Cover your mouth and nose when sneezing.

- Wash your hands regularly, especially after going to the bathroom or changing a nappy.

- Avoid deep kissing socially.

- DO NOT share lipsticks.

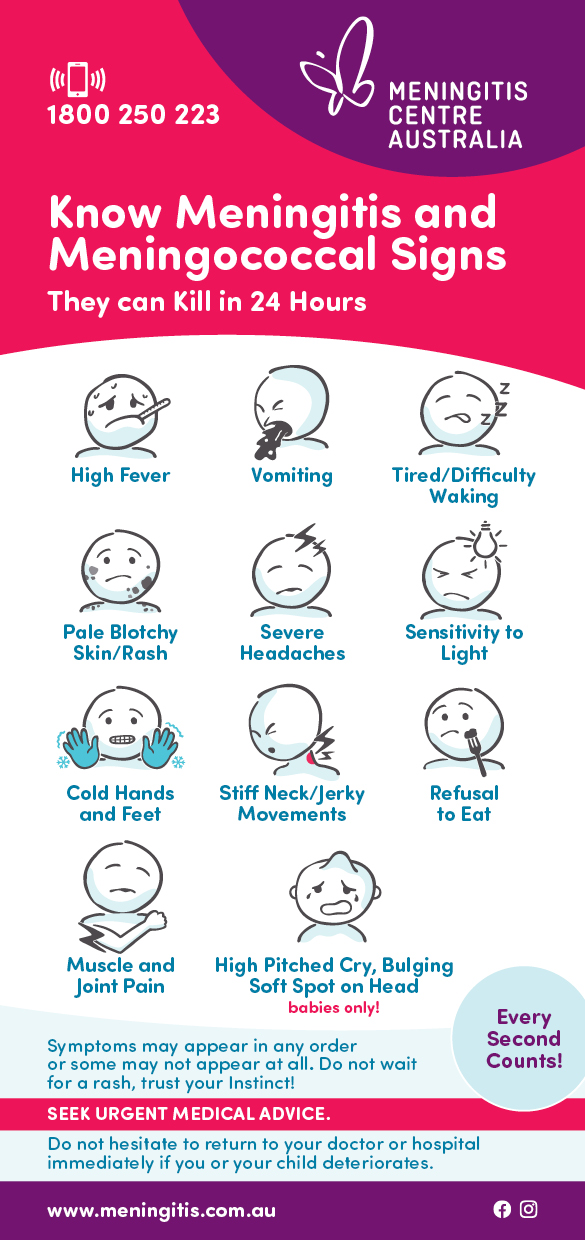

The best way to prevent Meningitis, Meningococcal, and Pneumococcal is through vaccination. However, it’s important to remember that not all strains are covered by vaccinations so, make sure you know the signs and symptoms AND IF YOU SUSPECT MENINGITIS, MENINGOCOCCAL OR PNEUMOCOCCAL SEEK URGENT MEDICAL ATTENTION.

Why are teens at risk?

There are several lifestyle factors and behaviours that are common among teens that increase their risk for Meningococcal:

- Increased social contact such as intimate kissing with multiple partners

- Crowded living situations such as dormitories

- Active or passive smoking

- Participation in mass gatherings such as sporting, social or cultural events involving large crowds

The best way to prevent bacterial meningitis is through vaccination. Not all strains are covered by vaccinations. So, make sure you know the signs and symptoms.

Vaccine Information

Meningococcal vaccines

Meningococcal vaccines protect against meningococcal disease

Polysaccharide vaccines are available to protect older children, adolescents and adults, from outbreaks or situations of increased risk (military recruits, university students, travelers). May be used in conjunction with antibiotics. These include:

- Combined groups A and C vaccine

- Combined groups A-C-Y-W135 vaccine

- Meningococcal B

Conjugated vaccines exist for routine immunisation of infants, children and adolescents. These include:

- Conjugate group C vaccine

- Conjugate groups A-C-Y-W135 vaccine

Pneumococcal vaccines

Pneumococcal vaccines protect against pneumococcal meningitis

A number of polysaccharide vaccines exist for routine immunisation of people over 65 years of age, for babies and those most at risk. Please refer to the National Immunisation Plan.

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B/Hib

Hib vaccines protect against Haemophilus Influenzae Type B.

The Hib vaccine is on the National Immunisation Plan in Australia and is given at 2months, 4 months, 6 months and 18 months.

Conjugated Hib vaccines are highly effective in preventing Hib disease and are recommended for routine use in all infants.

Vaccine Safety

Meningitis-preventing vaccines have proven to be extremely safe. Because they are composed of purified polysaccharide and protein, there is no possibility of contracting meningitis or any other infection from these vaccines.

Other things to remember include:

- Smoking can increase the risk of being a carrier of meningitis bacteria.

- Seasonal factors can also affect the incidence of bacterial meningitis. In temperate regions, the disease in the winter and early spring. In Sub-Saharan Africa, outbreaks occur in the dry season.

- Cases are more frequent in developing countries due to poverty, overcrowding and lack of access to vaccines.

- Anyone who has been in close contact with a meningitis patient within seven days before the onset of the disease is at increased risk of contracting it themselves. With meningococcal and Hib infections, preventative antibiotics are usually offered to close contacts. These reduce, but cannot eliminate, the risk of family members or other close contacts becoming ill.

Safe, effective vaccines are now available for many common types of meningitis and new vaccines are in development all the time.

Treatment

Diagnosis and treatment of meningitis varies from country to country, depending on access to medical care, availability of antibiotics and local antibiotic resistance patterns.

In order to diagnose meningitis, doctors may do a blood test and take a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the watery fluid that flows in and around the brain and spinal cord.

CSF is collected through a lumbar puncture and examined for the presence of white blood cells and bacteria. Blood and CSF samples will be cultured for the presence of bacteria.

Treatment should not be delayed for more than 1-2 hours while diagnostic tests are taking place.

Bacterial meningitis requires injectable antibiotics and fluid replacement. Transfer to a hospital with an intensive care department may be necessary.

If signs of septicaemia are present, treatment should be started as soon as possible. Diagnostic tests should be deferred until antibiotics have been given.

The choice of antibiotic will be based on the susceptibilities of the meningitis bacteria in each patient’s area. Because of the worldwide prevalence of penicillin-resistant pneumococci, ampicillin-resistant Hib and sulfonamide-resistant meningococci, treatment with a third generation cephalosporin (such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone) is the current standard of care.

In areas with high-level penicillin-resistant pneumococci, vancomycin is usually added until the susceptibility of the infecting bacteria is known. If patients are allergic to these antibiotics, chloramphenicol may be used as an alternative.

Antibiotics do not kill viruses. Although viral meningitis is more common than bacterial meningitis, treatment with injectable antibiotics should be started until a bacterial cause can be excluded. Treatment for viral meningitis is generally rest and pain relievers.

Recovery

Survivors of bacterial meningitis may require ongoing treatment or therapy after their recovery. Almost all patients with viral meningitis recover without any permanent damage, although full recovery may take weeks to months.

If you would like to receive our ‘After Effects – What happens next?’ Booklet or any other information, please contact 1800 250 223 or visit resources.